From the booklet ‘Lay Dominican Fraternities – A Way of Life’, published for the Jubilee year 2021

The founder of the Order of Preachers (also known as Dominicans) was St Dominic de Guzmán (1170-1221). He was a man of infectious enthusiasm. Everything he did was marked by a deep faith and an immense intellectual curiosity. In St Dominic, the yearning for union with God was inseparable from action in the world.

St Dominic’s way of life perfectly exemplifies the three dimensions of the Dominican vocation:

The total dedication to God in prayer and contemplation.

The cultivation of the mind through study.

The outflow of charity into apostolic action.

This sheds bright light upon one of the best-known Dominican mottos: contemplata aliis tradere (cf. St Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae III. Q. 40, a. 1, ad. 2.).

In this section of the Summa, St Thomas grants that in strict terms the contemplative life is more perfect than the active one. Nevertheless, an active life, which “by preaching and teaching delivers to others the fruits of contemplation, is more perfect than the life that stops at contemplation.” Indeed, “such was the life chosen by Christ.”

That is why Dominicans study the Word of God, driven by a thirst for the Truth (another motto of the Dominican Order is Veritas), which in turn makes the prayer-life of Dominicans a joyous self-giving – another way of defining Apostolate.

The requirement to study is central to the Dominican vocation and finds its origins in the earliest days of the Order. The early thirteenth century was a time when heresy was spreading at an alarming rate in many parts of Europe. People felt abandoned in the midst of what they perceived to be an increasingly detached attitude among the clergy and the hierarchical church. This led to violent clashes, including the preaching of crusades against heretics. When St Dominic came across the Albigensians (also known as Cathars) in Southern Europe, he was quick to understand that persuasion and reasoned argument were much more effective than any use of force. Study thus became central to the Dominican vocation.

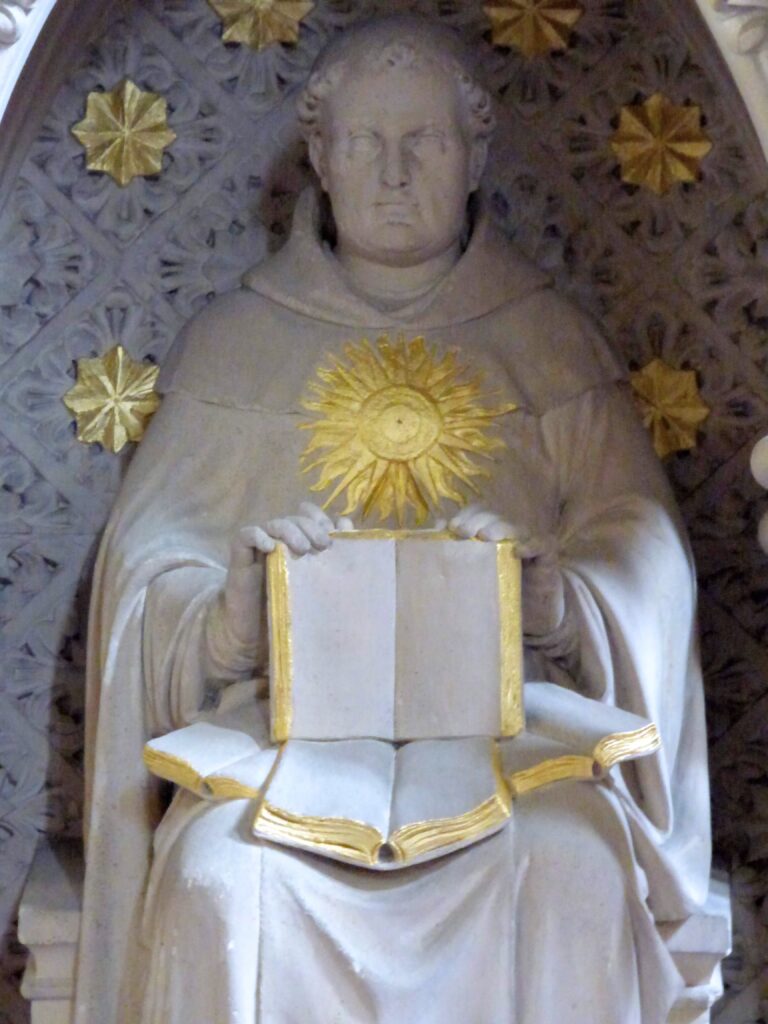

The attitude received its classic expression in the work of St Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), who brilliantly managed to strike a delicate balance between the various, often conflicting, intellectual traditions of his time. He argued against those who taught that human beings were primarily spiritual substances confined within the “prison” of the body by emphasizing the essential goodness of Creation. He was equally opposed to two conflicting tendencies, which nowadays we call idealism and empiricism. Against the purely theological ideal of knowledge, St Thomas acknowledged the autonomous rights of human reason and its scientific activity; and against the exclusivism of the ascetics, he defended the rights of human nature and natural morality.

Above all, Aquinas presented to his contemporaries a deep notion of intellectual enquiry as a long-term, cooperative pursuit. That is why Dominicans show little sympathy for any attempt to turn St Thomas into a repository of readymade answers to complex questions. There can be no doubt that St. Thomas loved the Truth passionately, but he was under no illusion that he could ever possess the Truth in this life. Every answer he gave, no matter how persuasive, was an invitation to reflection and further study. As a consequence, his method is the best vehicle for one of the most urgent needs of our age: the discernment of the signs of the times.